Fecal Dx antigen testing – find parasite infections the microscope misses

Diagnostic update • August 2020

Introduction

In order to ensure the health of patients, a faecal examination for intestinal parasites is an important part of a regular checkup. Regardless of the faecal procedure used, there can be some limitations on accurately identifying infections with some parasites. Detection of hookworm, roundworm, and whipworm can be difficult with the current diagnostics. IDEXX Reference Laboratories offers Fecal Dx antigen testing as an additional tool for detecting these common parasites.

Want to take it with you?

Background

In small-animal practice, hookworms, roundworms, and whipworms are commonly encountered intestinal parasites in

canine and feline patients. They each have a unique life cycle, and their prepatent period, the time in which they infect a host before laying eggs, may range from 14–21 days in hookworms, 14–30 days in roundworms, to as long as 74–90 days in whipworms. This prepatent period may allow infections to go undetected on faecal flotation, increasing the chance for the appearance of clinical signs prior to evidence of eggs in the stool.

Prevalence

In dogs and cats, the prevalence of infection with each intestinal parasite varies from region to region and tends to occur more frequently in shelter animals than in homed dogs and cats that visit the veterinarian on a regular basis. Outdoor pets and those that consume prey with possible infective larvae in their tissues are also more likely to be infected.

Australian studies have shown that hookworm and roundworm prevalence in pet dogs was 3.9% and 0.6% respectively, and 10.7% and 2.4% in shelter dogs.1 For cats, 1.7% of owned cats and 4.9% of shelter cats were infected with Toxocara cati.1

The whipworm prevalence in dogs in Australia, based on detection of eggs in faeces, ranges from 0.9% in pet dogs to 3.1% in shelter dogs.1 Whipworm infections in cats are rare.2

Clinical signs

Some dogs and cats infected with these common intestinal parasites may be asymptomatic, but others may develop a variety of gastrointestinal signs that depend on the parasite and age of the patient. Symptoms may range from mild diarrhoea, vomiting, and ill thrift to severe bloody diarrhoea, anaemia, and occasionally death.

Current Diagnostics

Currently, the most common method for diagnosing intestinal parasite infections is faecal flotation, either passive or by

centrifugation. There are many issues that may complicate the diagnosis of infections with this method. One possible

complication is misidentification. Pollen and other debris may be misidentified as eggs. In addition, the inappropriate identification of eggs from other species as a result of coprophagy (the ingestion of infected faeces) may also occur. One study researching this occurrence found that 31.5% Toxocara‑positive canine faecal specimens were in fact T. cati eggs.3

Another common problem concerns the varying density of the different eggs, which makes it difficult for a clinician to select the ideal faecal flotation solution to ensure adequate recovery of eggs from all potential parasites.

Yet another challenge with faecal flotation is that this method of egg identification lacks the ability to detect infections during the prepatent period or with single-sex infections, when eggs are simply not present in the infected animal.

Finally, faecal flotation may not always be reliable as a single test. Because many parasites shed eggs intermittently, a specimen from an infected animal may still generate a false-negative diagnosis if only a single faecal flotation is examined. For all these reasons, there is a need to find a better tool for the diagnosis of the most common intestinal parasites found in dogs and cats.

New testing options from IDEXX Reference Laboratories

Antigen detection is commonly used today to diagnose Giardia infections, and now it is available for these additional parasites. IDEXX Reference Laboratories has developed Fecal Dx antigen testing, which includes enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) for the detection of hookworm, roundworm, and whipworm antigens in faeces. These antigens are secreted by the adult worm and are not present in their eggs, which allows for detection of prepatent stages as well as the ability to overcome the challenges of intermittent egg laying. This early detection during the prepatent period will also reduce the frequency of environmental contamination with potentially infectious eggs. As recommended by the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC), faecal tests for antigen should be combined with microscopic examination of faeces for eggs for the widest breadth of detection of intestinal parasites in dogs and cats.4

Detect more infections

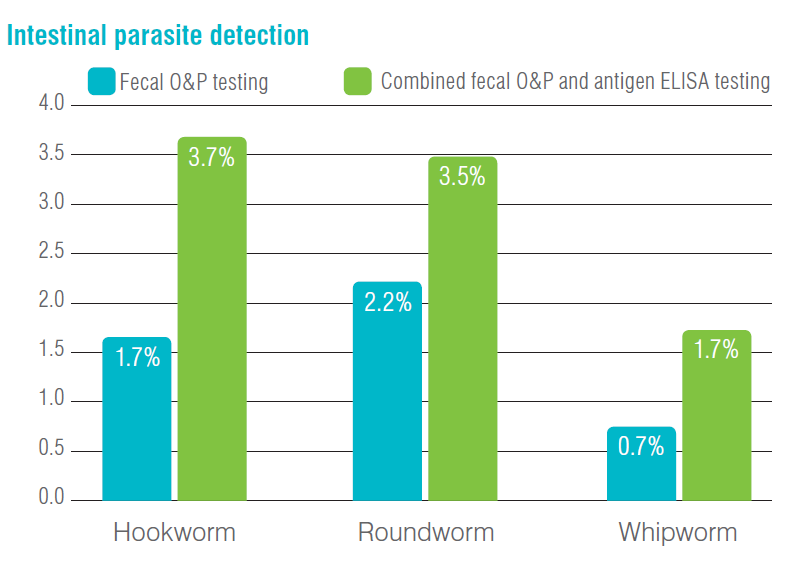

More than 750,000 IDEXX Reference Laboratories faecal results, consisting of both canine and feline specimens, were analysed for positive nematode results. These specimens were submitted for testing using both faecal flotation by centrifugation (faecal O&P) and faecal antigen ELISA methods for hookworm, roundworm, and whipworm.

Hookworm eggs were detected in 1.7% of the specimens. The hookworm-specific antigen ELISA was positive in an additional 2.0% of specimens that were negative for hookworm eggs, thus bringing the total hookworm detection with the combined faecal O&P and antigen ELISA testing to 3.7%.

Roundworm (ascarid) eggs were detected in 2.2% of the specimens. The roundworm-specific antigen ELISA was positive in an additional 1.3% of specimens that were negative for roundworm (ascarid) eggs, thus bringing the total roundworm detection with the combined faecal O&P and antigen ELISA testing to 3.5%.

Whipworm eggs were detected in 0.7% of the canine specimens. The whipworm-specific antigen ELISA was positive in an additional 1.0% of specimens that were negative for whipworm eggs by faecal O&P testing, thus bringing the total whipworm detection with the combined faecal O&P and antigen ELISA testing to 1.7%.

Detect infections earlier

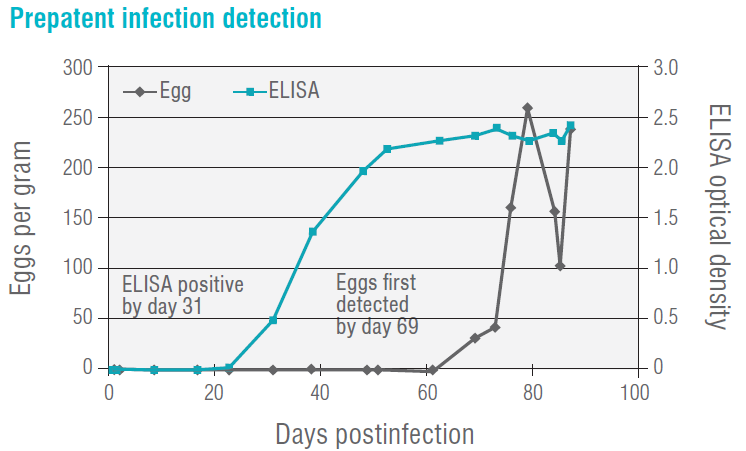

Because of the lack of egg detection with faecal O&P testing during the prepatent period and single-sex infections, many

parasite infections may go undetected for a period of time and, therefore, create a difficulty in correlating clinical signs to faecal test results. In an experimental infection study conducted at IDEXX, the faecal antigen ELISAs were able to detect infection during this prepatent stage.

The graph below illustrates the identification of a whipworm infection approximately 30 days before faecal O&P testing when using the whipworm-specific antigen ELISA.

Treatment

There are a variety of anthelmintic products available for both treatment and control of hookworm, roundworm and whipworm infections. Please see the current Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC) recommendations for guidance.6

Fecal Dx antigen testing detects worm antigen. A positive antigen test indicates infection. Antigen-positive and egg-negative specimens can be seen during the prepatent period, with single-sex infections, and as a result of intermittent egg shedding. Microscopic identification of eggs in antigen-negative specimens may be due to ingestion of infected faeces (coprophagy) or because the amount of antigen is below the level of detection. Treatment should be considered for patients found positive by either antigen or egg detection.

Public health considerations and preventive measures

Because of the zoonotic potential of these parasites, most commonly hookworm and roundworm, immediate disposal of faeces is important. This will also reduce the likelihood of reinfections and prevent the long-term contamination of the environment. Monthly anthelmintic medications can be helpful in preventing the continuation of the cycle.

Ordering information

Test name and contents

Fecal Dx Antigen Panel

Hookworm, roundworm, whipworm and Giardia antigens by ELISA

5 g fresh faeces in a clean plastic container

Contacting IDEXX

Customer Support

If you have any questions regarding test codes, turnaround time or pricing, please contact our Customer Support Team at 0800 838 522.

Expert feedback when you need it

Our Internal Medicine Specialist consultants are available for expert and complimentary consultation. Please call 0800 838 522 if you have questions.

Recommended reading

Elsemore DA, Geng J, Flynn L, Cruthers L, Lucio-Forster A, Bowman DD. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for coproantigen detection of Trichuris vulpis in dogs. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2014;26(3):404-411.

Elsemore DA, Geng J, Cote J, Hanna R, Lucio-Forster A, Bowman DD. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for coproantigen detection of Ancylostoma caninum and Toxocara canis in dogs and Toxocara cati in cats.J Vet Diagn Invest. SAGE Journals website. Published 19 April 2017. Accessed 16 June 2017.

Research update

References

- Little SE, Johnson EM, Lewis D, et al. Prevalence of intestinal parasites in pet dogs in the United States. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166(1–2):144-152.

- Blagburn BL, Lindsay DS, Vaughan JL, et al. Prevalence of canine parasites based on faecal flotation. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet.1996;18(5):483–509.

- Gates MC, Nolan TJ. Endoparasite prevalence and recurrence across different age groups of dogs and cats. Vet Parasitol. 2009;166(1–2):153-158.

- Bowman DD. Georgis’ Parasitology for Veterinarians. 9th ed. St Louis, MO: Saunders; 2009:224.

- Fahrion AS, Schnyder M, Wichert B, Deplazes P. Toxocara eggs shed by dogs and cats and their molecular and morphometric species-specific identification: is the finding of T. cati eggs shed by dogs of epidemiological relevance? Vet Parasitol. 2011;177(1–2):186-189.

- Companion Animal Parasite Council. Current advice on parasite control: intestinal parasites. www.capcvet.org/capc-recommendations. Accessed 8 November 2016.

The information contained herein is intended to provide general guidance only. As with any diagnosis or treatment, you should use clinical discretion with each patient based on a complete evaluation of the patient, including history, physical presentation and complete laboratory data. With respect to any drug therapy or monitoring program, you should refer to product inserts for a complete description of dosages, indications, interactions and cautions.